By Robert Tracy McKenzie | Amazon.com | 304 pages

Published in September of 2021

SUMMARY: What if the way most Americans understand democracy is fundamentally flawed? What if the vast majority of Christian views of human nature has blended with popular culture? What if this misunderstanding has resulted in idolatry and hubris? In We the Fallen People, author Robert Tracy McKenzie digs into the past for insight into our present political morass.

McKenzie says that we must first rid ourselves of two deep-seated beliefs about democracy in America.

“We must renounce democratic faith, our unthinking belief that democracy is intrinsically just. We must disavow democratic gospel, the ‘good news’ that we are individually good and collectively wise.”

To begin rejecting the ideas that people and democracy are inherently good we need to take an honest, critical look at history through a Biblical lens – something that McKenzie says Christians, and Americans in general, are poor at. McKenzie tells us we are “present-minded” people disconnected from the past.

“Our historical amnesia contributes directly to our dysfunctional engagement with contemporary politics,” McKenzie pens. “A pattern distinguished chiefly by its worldly pragmatism and shallowness.”

In other words, Christians are not distinct in how we view, learn, or apply the lessons from history or engage in our current cultural moment. We are caught up in partisanship and petty bickering just like everyone else. As a result, “We are giving the culture a reason to view followers of Christ as simply one more interest group, one more strategically savvy voting bloc willing to trade political support for political influence.”

Breaking this cycle starts with putting on our big girl or big boy pants, rejecting simplistic answers and banal platitudes, digging into history and the Bible, and starting to have grown-up conversations.

“We must think deeply before we can act effectively,” McKenzie says.

McKenzie leans heavily on Alexis de Tocqueville‘s observations from his seminal Democracy in America. The Frenchman traveled to America in 1831 on a 10-month observation tour of American democracy. Perhaps Tocqueville’s most crucial observation was his definition of democracy.

“The key is Tocqueville’s insight that democracy is morally indeterminate instead of intrinsically just,” McKenzie says. “If democracy is the implementation of the will of the majority, then whatever the majority wills is ‘democratic.'”

This was a paramount concern to the framers of the Constitution, who believed in a variety of traditional and non-traditional Christianity, but most certainly believed in original sin or, at the very least, that people will look after themselves rather than others if given the chance.

“They designed a Constitution for fallen people,” McKenzie says. “Its genius lay in how it held in tension two seemingly incompatible beliefs: first, that the majority must generally prevail; and second, that the majority is predisposed to seek personal advantage above the common good.”

Those two facts – that democracy is not intrinsically just nor are people inherently good – should be an easy pill to swallow for Christians. The Bible is clear that we are sinful beings (Rom. 5:12, Eph. 2:3), and yet we have an extremely difficult time accepting that fact.

Just forty-three years after the ratification of the Constitution, Tocqueville was starting to see the seeds of what is now a sprawling, rotting tree: individualism, support for populist candidates, the mixing of politics and religion, sermons speaking of platitudes, the insatiable desire for wealth, a shallow faith, the centering of self, and the prosperity gospel. Sound familiar?

During Tocqueville’s time in America, Andrew Jackson was the president of the United States. He is seen as the first populist president of the U.S.A. He was the first to espouse the belief that the majority makes the right decision. He was combative. He was partisan to a fault. There are numerous correlations between Jacksonian America and today’s America. Many of these beliefs are so engrained into our culture it is hard to recognize that it has not always been this way.

“It’s hard to think Christianly about values that we have taken for granted for so long that we’re no longer even aware of them. This is where historical knowledge becomes invaluable. At its best, our engagement with the past can help us to see the present–and ourselves–with new eyes.”

Those new eyes require us to acknowledge America’s missteps and failings. To not act defensively. To humbly look at the good and the bad of history. Ultimately, it should transform our behavior and thinking. What does this specifically mean for Christians?

In light of the Bible, McKenzie suggests four practices. First, we must run from every effort to meld Christianity with a particular political party, movement, or leader. Second, we must confess the allure and danger of power. Third, we must work proactively to mitigate the abuse of power. Fourth, rhetoric matters.

“Our words reveal who we are, Jesus proclaimed in the Sermon on the Mount, for they flow ‘out of the abundance of the heart.’ But our words also teach by example.”

One aspect that we heartily appreciate about McKenzie’s writing is not only is he teaching the reader about history, but he is also teaching the reader how to learn, approach, and apply the lesson from history from an honest and faithful Christian perspective. Don’t hesitate to pick up this book.

KEY QUOTE: “A powerful majority pursuing its self-interest may oppress the minority. But Tocqueville also wants us to see that, because we’re fallen, a powerful majority pursuing its self-interest can also gradually forfeit its own liberty. He envisions a servitude in which ‘each individual allows himself to be clapped in chains.’ He sees an ‘innumerable host’ of individuals, ‘all alike and equal, endlessly hastening after petty and vulgar pleasures with which they fill their souls. Each of them…is virtually a stranger to the fate of all the others. For him, his children and personal friends comprise the entire human race.’ Tocqueville labels this decay of the community ‘individualism,’ and he believes that it is a predictable if not inevitable feature of a democratic society.”

BONUS: Listen or watch McKenzie talk about this book at Wheaton College.

DID YOU KNOW? Sunday to Saturday has a Goodreads page where we post all of the books we have read – even the ones that didn’t make the cut.

Our latest curated content on history:

BOOK: This Land is Their Land

Most Americans have learned about Thanksgiving with the Pilgrims at the center of the story. A story about a people fleeing religious persecution and landing on the shore of a wild, uncivilized country where they are befriended and saved by kind natives. The Pilgrims and the natives celebrate Thanksgiving and live happily ever after. It…

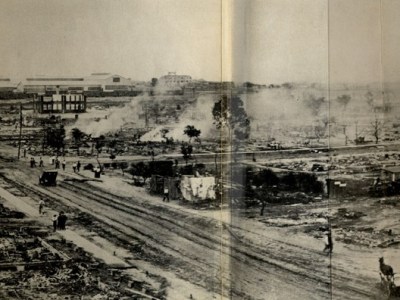

LEARNING CAPSULE: Tulsa Race Massacre

Over $1.5 million dollars of damage wiped out 35 blocks of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921 as thousands of white people looted and killed hundreds of Black people. Learn about this often overlooked part of American history.

BOOK: Unsettling Truths

Exceptionalism. Triumphalism. White Supremacy. Mythology. These are just a few of the words that are the bedrock of the United States of America and the white American church. The blending of Christianity with conquest dating back to the 1400’s to the Doctrine of Discovery influencing the racist and sexist wording of the Declaration of Independence…